Q1: Now that Wild Honey is off to print, are you feeling proud of it?

Yes, a thousand times yes. But also a tad anxious.

Q2: It’s a huge book and it’s been a monster project. Where did the idea for it first come from?

My university degrees considered Italian women writers, but when I left university I focused on my own poetry. I carried the Wild Honey seed from those days because New Zealand women poets felt like an unwritten story. All roads — my university life and my poetry life — led to Wild Honey.

Q3: How long has it taken you?

Four years writing and researching, but decades germinating.

Q4: It must have been a massive process of discovery. Tell us about one poet you are pleased to have come across and to have shone a spotlight on?

There were so many discoveries. Familiar poets appeared in surprising new lights as I lingered over their work, such as Fleur Adcock, Robin Hyde, Ursula Bethell, Nina Mingya Powles, Karlo Mila, Hinemoana Baker, Tusiata Avia, Alison Wong, Fiona Kidman, Emma Neale, Anna Jackson. I wanted to write whole books about each poet. I loved the work of Evelyn Patuawa-Nathan, unfamiliar to me, but was disappointed I could find only one book published in 1978. I wanted more!

Shining a light on Blanche Baughan was a delight. At first her poetry felt impenetrable, but then as I spent time in the archives, and her biography unfolded, her poems sang for me. She wrote from both heart and intellect, daring and empathy. Her extraordinary life story hides in traces in her poems as do her strong political ideas.

Q5: Not only is it, in many ways, a ‘lost poetry recovery project’ but it’s also a major biographical treasure trove. Some of these women had extraordinary lives. Who stands out for you?

Robin Hyde and her drive to write poetry through all obstacles, her need to earn money to pay for her son’s care, her ongoing physical pain, her maternal pain, her estrangement from and attachment to New Zealand. Her poetry bears traces of all this. It is profoundly moving.

I was also moved by the intense love that fuelled Ursula Bethell as she wrote and the way she could not write when the love had gone; by the political fierceness and poetic daring of Blanche Baughan and Jessie Mackay. Extraordinary women. And the way some women wrote one stunning collection, such as Mary Stanley, and then disappeared as poets, and their biographies felt incomplete.

Q6: What do you hope readers will learn from this book?

To discover their own pathways through a poem and experience the joy of poetry. To experience the width and richness of women’s poetry within our diverse poetry communities. To appreciate multiple styles, subjects, preoccupations.

Q7: What do you hope its contribution to our understanding of our literature will be?

That poetry is open; that we need not adhere to fixed models of reading, writing and critiquing poetry. That women have written ceaselessly and gloriously despite ongoing misreadings and devaluations during the twentieth century. That women write in myriad ways of myriad things in poems, but that personal, domestic and maternal subject matter will never be redundant.

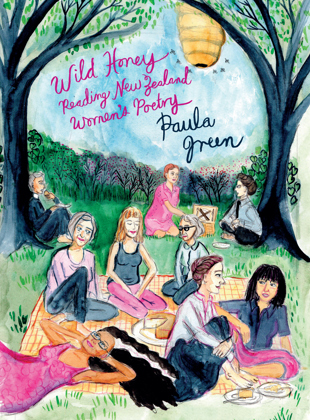

Q8: Can you tell us a bit about the beautiful back and front cover?

Sarah Laing, fiction writer and graphic artist, painted a group of barefoot women poets picnicking outdoors: Anna Jackson is reading in a tree; Tusiata Avia and Hinemona Baker are conversing, as are Alison Wong and Ursula Bethell, and Robin Hyde and Blanche Baughan. Selina Tusitala Marsh is stretched out gazing at the sky; Jenny Bornholdt and Jessie Mackay are daydreaming; Michele Leggott is hugging her guide dog; Elizabeth Smither, Airini Beatrais and Fleur Adcock are mid conversation. I love the mood and I love the connections; it references the way I have been musing and conversing (taking tea) with women’s poetry over the past four years.

Q9: And about the notion of dividing its sections into rooms?

I wanted to build a house for women that then opened onto the wider world. I began with the foundation stones (Jessie Mackay, Blanche Baughan and Eileen Duggan) and then moved into rooms. As I entered a room (or feature such as the hearth or the shoe closet) I took a few women poets with me and each room became a place of discovery. I wanted to refresh the domestic (so long denigrated) and advance the way women’s poetry is alive with heart, intellect, invention, rebellion, homage. To move beyond the house — to the garden, the countryside, the city and the sky — underlined the infinite possibilities of women’s poetry.

Q10: What are you reading at the moment, for work and for pleasure?

I recently read Tina Makereti’s The Imaginary Lives of James Poneke and loved it so much I wrote about it on by blog Poetry Shelf. I am currently loving Mary Kisler’s Finding Frances Hodgkins so will write about that book too. I am rereading the poetry of Anne Michaels, having worked with her on the Sarah Broom Poetry Prize, and feel such intense connections with her poems I’m writing a long piece for my blog. Her children’s book, The Adventures of Miss Petitfour, has become an all-time favourite with its word agility and breathtaking imagination. I have just read a terrific suite of local poetry collections: Victoria Broome’s How We Talk to Each Other, Ashleigh Young’s How I Get Ready and Murray Edmond’s Back Before You Know. I also loved Vaughan Rapatahana’s two-part article on Kiwi-Asian women poets at Jacket2. I am about to read Max Porter’s Lanny and Annie Erneaux’s The Years. Cookbooks, always cookbooks.