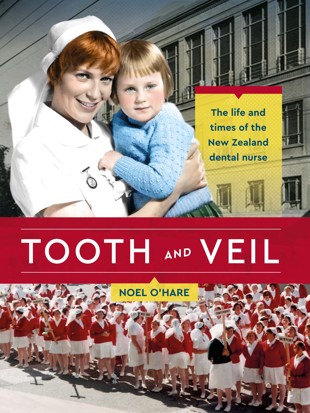

Tooth and Veil

NOEL O'HARE

Introduction

Shop assistants working along the ‘golden mile’ in Wellington had witnessed many marches down Lambton Quay over the years: rowdy protestors against the Vietnam War, apartheid and nuclear testing in the Pacific; Jesus marches with Salvation Army bands; rallies for Māori and women’s rights.

They waved flags, hoisted placards and banners, spilling onto the pavements and stopping traffic. The bullhorn-led chants, shouts and jeers, amplified in the narrow street by the tall buildings on both sides, made it impossible to attend to customers and there was nothing for it but to wait until the protestors had passed and the noise subsided.

The school dental nurses’ march on a sunny autumn day in 1974 was different. It was, one observer noted, ‘almost certainly the largest organised demonstration of women since the days of the suffragettes’. Shop assistants and passers-by had never seen anything like it: young women marching four abreast in starched white uniforms, veils and red cardigans. There were no placards protesting this or demanding that, just small signs held aloft at intervals stating which part of the country the women hailed from: Northland, Auckland, Waikato . . . a geographical spread that finished with Timaru, Dunedin and Invercargill. And most impressive of all was the silence. A powerful hush that made you strain to listen, to understand.

They were far from typical protestors. Most were middle-class, the daughters of farmers, accountants, businessmen and lawyers — conservative folk who deplored street politics and could be relied on to vote National. Many of the marchers had never been to the capital, and certainly never envisaged that on their first visit they’d be parading down the main shopping street while bystanders stared. It felt weird. Since the first day they’d reported for training, the rule had been stressed: the wearing of the uniform in the street is not permitted. This was disobedience, rebellion. Who knew the consequences when they returned to their clinics? It made some nervous, but there was comfort in numbers: 600 of their colleagues were marching with them.

They were the least militant group of workers. However, like a long-suffering partner in a relationship, there’d been some ‘That’s it!’ moments when suddenly the hurts, slights and indifference had become too much to bear.

Pay was ostensibly why they were marching. For 30 years their wages were tied to those of public health nurses in a system of relativity. Any pay rise either group negotiated was passed on to the other. This had not always worked in the dental nurses’ favour, as some pay claims were rejected because it would have put them ahead of public health nurses.

However, in 1973 public health nurses negotiated a big backdated pay increase and dental nurses expected to receive a similar boost. Then, in an about-turn, the State Services Commission (SSC) declared that relativity was no longer relevant and it did not intend to break the wage freeze by passing on the increase to the dental nurses.

Much as they were upset by the State Services Commission’s duplicity, pay relativity was not what many of the marchers cared about or even understood. It was merely the instrument that lanced the boil of anger and frustration that had been building for decades. For more than 50 years, dental nurses had endured a workplace milieu in which they’d been treated as inferior beings, discouraged from thinking for themselves and subjected to petty military-style discipline. ‘You learned from an early stage that you were a dental nurse, slave of the dental profession,’ remembers one nurse.

Previous generations of dental nurses had stoically accepted their lot, but times had changed. The marchers had grown up in the radical free-wheeling 1960s (though the subversive virus took a long time to reach New Zealand). The School Dental Service, on the other hand, had calcified in the late 1940s, and the military style of management grated with new intakes of dental nurses. They were tired of having to stand to attention with hands behind their backs when addressed by a superior, tired of the unscheduled inspections of their clinics to catch them out for petty failings like dust on a high ledge or a scuff mark on their white shoes, tired of the starched uniforms and veils that chafed their skin and made a mess of their hair, tired of being transferred on a week’s notice from Auckland to Haast and discovering the caravan where they were to live was also occupied by four fisheries officers, tired of the antiquated equipment they had to use, tired of inflicting needless pain on children because the Health Department allowed the low-strength anaesthetic they supplied to be used for extractions only, not fillings. They were tired of the epithet ‘murder house’ and of being slagged off for doing ‘unnecessary’ work on patients.

As the marchers reached the end of Lambton Quay, they passed, on their right, the Old Government Buildings. It was there, in an annexe known as the Tomato House, that the first dental nurses had trained. Colonel Thomas Hunter had founded the School Dental Service in 1921. The colonel, who’d led the New Zealand Dental Corps in the First World War, was appalled at the state of children’s teeth in New Zealand, a large percentage of whom needed extractions and/or fillings. As this book will show, despite opposition from many dentists and a lack of funding, the service thrived, a unique New Zealand social experiment that would be lauded around the world and modelled in 15 countries.

In 1940, 295 dental nurses were in training when the Dominion School for Dental Nurses and Children’s Dental Clinic opened in Willis Street, Wellington. The new clinic was a wonder of the dental world. In a room the size of a rugby field, with six- metre-high windows, more than 50 children could be drilled and filled at the same time. Health experts, foreign delegations, even royalty visited regularly, escorted through the building by senior staff. ‘We were never introduced to overseas guests; it was always the men,’ one dental nurse recalled.

If they’d been asked what it was like being a dental nurse, what stories they could have told. Those first precarious years when the whole world seemed to be set against them: the press, the medical establishment, dentists, even parents. The loneliness of pioneering dental nurses sent to the backblocks to set up makeshift clinics. The privations of the Great Depression, and how once, after work, they’d picked their way through broken glass along Lambton Quay after the unemployed could curb their desperation no longer and had rioted. Then came the war and the move to the new Willis Street clinic, from the roof of which they’d watched excitedly as American troopships arrived at the Wellington docks. By then they were living in hostels around the city, one a former brothel. At night, drunken soldiers who hadn’t caught up with the change in occupancy would come knocking.

Conformity had been the watchword of the uptight, strait-laced 1950s. Schools were bursting at the seams with the baby boom, and it was a hectic time with so many teeth to drill and so few dental nurses. Then there was the dizzy, turbulent, miniskirted 1960s, when training to be a dental nurse felt like stepping back in time. And now here they were, massed on the steps of Parliament while photographers and television news cameramen jockeyed for position to capture the drama. The prime minister, Norman Kirk, had agreed to meet them. ‘Parliament Invaded by Dental Nurses’ ran the headline in the Evening Post: ‘The deputation moved into the building to go to the Prime Minister’s suite. The nurses moved to follow them. Parliament messengers and police blocked their way. So the nurses went skirmishing. They found unguarded doors and surged in a white wave into the corridors.’

As dental nurse Annette King reflected later: ‘We were a bunch of women who had never done anything like that. We were nice girls — that was the sort of label we had.’

How had it come to this?