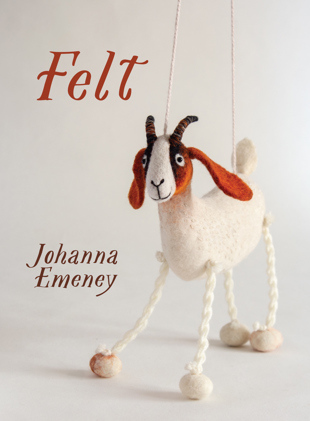

Q1: First things first: the beautiful cover. Tell us the story of this adorable felt goat.

Yes, isn’t she beautiful. Her name is Grethe, and she was made by the talented marionette-maker Olga Kupunia of Georgia (the Republic of Georgia, Caucasus), who kindly allowed me to use her image. I think that the sweet approachability of the Grethe image is delightful. I also love the fact that she is attached to strings, adding a little nuance.

Olga and I share an obsession with nature, animals and the education of young people through story. Grethe now lives in the bedroom, looking over me and David in a very altruistic (sometimes quizzical) way.

Once the collection was assembled, I knew that it had to be called Felt, and the cover had to feature a felted goat. I sometimes get the same sort of compulsive feeling when I am writing a poem: this poem must be in such-and-such a frame and it must take this voice, for example.

There are quite literally poems in the collection about goats and featuring felted figures which were used by a teacher to tell Bible stories to our junior school class. However, more than that, there are poems about the things which are unforgettably encountered through the senses — and not always actively. Poems about the sort of experiences that are corporeal as well as emotional — physically moving. I wanted the title and the image to express all of those things.

Q2: Your first volume of poetry, Apple & Tree, was published in 2011. Is it still as exciting to be bringing a new collection into the world?

There is nothing quite like having your first book published. In many ways, I reckon the launch and the radio interview are the best things you will ever experience, because you get a chance to tell a room full of people how you feel about them and then you are allowed to read them some of the most personal and important things you have written. A week or two later, you can explain your vision of the world to 300,000 people, and say the names of your friends and mentors. It is a chance to share and be thankful in a way that not many people are granted in a lifetime.

My first journey to publication coincided with having met Dame Chris Cole Catley, whom I rang on a self-dare one day, having read an article about her in the paper and fallen instantly in love. In a matter of weeks, she became not only my publisher, but also a terrific mentor and friend. In a few months’ time, she’d brought me in with her and Ros Ali, facilitating the Michael King Young Writers Programme, and both she and Ros taught me decades in just a few years. My book was Chris’s last launch.

My second collection, Family History (Mākaro Press, 2017), was exciting in another way because, this time, I had challenged myself to tell a single story via many poems — and this book is a homage to my late mother, so very special. I had ensured that nearly every poem gained publication in a magazine or journal before the collection itself was assembled. I wanted them to prove their ability to stand alone in advance of being read as part of a longer narrative.

Family History was also a significant collection to me as it had a point to make about the importance of personalised medicine and assisted dying. Three launches courtesy of the amazing Mary McCallum and another interview with Kim Hill gave me the chance to share poems about my adored mother, and to put forward a point of view about these things in a way that was neither polemical nor dogmatic. I think this is what autobiographical poetry which is collected as a narrative can do: it allows people to understand a single story and apply it universally. I’m not saying that it changes minds; it just opens minds to new ideas much as introducing someone to a person who has had a particular experience might.

Q3: How do you feel you have developed as a poet?

I think I have become more confident and adventurous. I’ve certainly tried to embrace the awkward a little more, because I do believe that the best poems are where the awkward facts and feelings are. I have also strayed away from the autobiographical and inhabited a few other bodies and minds in a few of the Felt poems. I suppose that might be what empathy is when you translate it into writing. I would hope that I’ve kept the plain-spokenness that I started out with, and which people who don’t normally like poetry have said that they enjoy about mine.

Q4: When did the idea for this new collection first surface, and did you have a sense of its shape from the outset?

The idea for a new collection comes, for me, when I have about half of the poems, and they are all tracking along the same lines.

It sounds like a cliché, but I wanted these poems to be moving and memorable. I wrote them to be explorative, and to test the line between emotionality and sentimentality. I think feelings are very corporeal things, and so hard to put into words without sounding trite.

I certainly didn’t have a sense of the book’s shape at the beginning, but I always knew it would have some ‘little stories’ going on in it. There would be, for example, some poems following an erstwhile student, some looking at the end of a long friendship, some looking at a marriage in crisis, and others just wandering around observing animals (who, of course, are super-sentient) — much as I do on a daily basis!

Q5: The attentive reader will note how the linked poems first announce themselves and then fade out as another sequence emerges. Were the poems within each sequence written relatively contemporaneously?

Several of the most obvious sequences were written each as a group, yes. There should be a feeling of ‘story’ in there, so that you are left, as the reader, to fill in what has happened in between. They happen like that because when I am, myself, in the middle of an unfolding predicament, or watching one unfold, I suppose my writing is almost diaristic. In other cases, for example the ‘animal poems’, you would be quite right to think that I’m writing these very frequently. Sometimes a poem about the natural world will turn into a poem about human nature because of one’s preoccupations (or just because of the magic way in which poetry works as one is writing it) and other times, an animal poem will stay just as it is, observational.

Q6: How do you make the decision about which poem goes first?

I usually go for something that will catch the attention, that is short and tightly structured but layered, too, offering a little intrigue. In this case, I chose ‘Suspicion’, which starts off one little story sequence. It is ostensibly a description of a boy chasing a seagull, but it also lends itself to other readings:

Suspicion

The seagull walks more quickly

in front of the little boy

whose hands are a gun.

She will not fly or stop

to look behind;

she will just keep a hop

ahead of his shadow

until he loses interest.

Because he will lose interest.

He will lose.

He will.

Q7: And how do you know when it is done?

It feels like a satisfying sandwich made with the bread and fillings you like most. You might take a lettuce leaf out and put a slice of tomato in, but on the whole, it looks appealing to your appetite. You feel that this would be an acceptable sandwich to others. They may even like it as much as you do.

Q8: When do you write, and where?

I usually write poetry when I have an urge or itch to do so, irrespective of location. I do need quiet usually, though, and a stretch of time if I’m looking to complete a single piece. Sometimes, however, I will write with a class of students, using the energy in the room to help me.

Q9: Are you ever not writing poems?

As well as the odd poem, I am writing a young people’s book with my friend Sarah Laing at the moment. It is about the recently retired Bird Lady, Sylvia Durrant (and, following Sylvia’s lead, how we can care for our birdlife). It’s terrific fun, collaborating with someone and not writing alone. I also write non-fiction (most recently a chapter about disability and poetry for Routledge) and, of course, I’m teaching during the university year — creative writing at Massey. One of the most enjoyable courses is ‘Starting Your Manuscript’: I get to read the most marvellous work-in-progress by third year students who aspire to publish all sorts of books — YA, fantasy, poetry, crime. So, I am allowed to write lots of notes on those manuscripts, as well as feeding back to the authors in online workshops.

Q10: Whose poetry are you reading right now?

Mary Jean Chan — her collection Flèche (Faber & Faber, 2019) has all of the things I like in terms of themes and structural innovation. Natalie Diaz, whose Postcolonial Love Poem was shortlisted for the Forward prize (along with our own Nina Mingya Powles’ 木蘭 Magnolia). My favourite of her books is When My Brother Was an Aztec (2013). The tenderness and anger expressed in these poems are so real and palpable.