Q1: What prompted you to begin the Conversātiō book project?

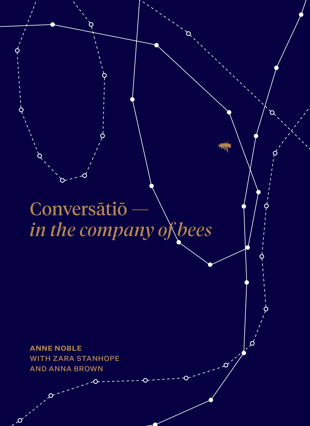

Following the inclusion of Conversātiō and a suite of my other works about bees in the 2019 Asia Pacific Triennial, Zara Stanhope, who was then curatorial manager at the Queensland Art Gallery and lead curator for APT9, suggested we do a book together about all my bee projects. The idea had never occurred to me, but as the bee works at APT9 seemed to attract a large and varied audience, the idea of a book offered a worthwhile challenge to bring all the series of bee works together in an interesting new way.

Q2: Is it, in some ways, a conclusion to your long-time practice focussed on bees and their remarkable lives?

I have been working with bees for 10 years now — and loved making them a focus of my work. Influenced, I am sure, by the nature of the bees themselves, all my projects have become more and more collaborative over time. This book became a wonderful way to reflect on the journey and include within it all the various contributors and participants who became part of creating the artwork Conversātiō — which sits at the heart of the book.

Q3: You gathered an impressive team of collaborators. What strengths did Zara Stanhope bring to the book project?

Zara is a fine curator who supports artists in a way that inspires them to pull out all the stops. She lent her curatorial acumen to the project and together we finessed the concept for the book in tandem with Anna Brown, our designer.

Q4: And the book’s designer, Anna Brown?

We worked collectively throughout to progress the content and the design — an unusual but wonderful way of working given that design so often comes at the end of the project, when the content needs a designer on board to create the book as an object, almost like an afterthought. This book was entirely collaborative, and Anna was a part of the team from the outset — contributing to its conceptual development as a book that is much more than a catalogue of a series of artworks.

Q5: Like any colony of bees, isn’t it the case that a team of focused, specialised helpers worked with you on Conversātiō itself?

Bees are the inspiration for my observations and reflections on the complexity of living systems throughout a number of photography, video and installation projects. The work Conversātiō, which is also the title of the book, places the practice of listening attention at its heart. The idea to bring a live colony of bees into the gallery with its home in the centre of an art work could not have been realised without the collective minds of artist, scientists, beekeepers, designers and the community of gallery staff who engaged over six months, activating experiences of bees for the public. What we hope the book achieves is

Q6: What’s the most amazing honey you have ever tasted?

I love the way honey tastes so clearly of its source. In our valley the honey flow coincides with native plants that flower from December to January — rewa rewa, rata, kamahi and a bit of manuka — and this mixed bush honey is amber coloured and finely flavoured. Some years, though, when it is wet in December and the bees don’t forage much, pōhutukawa, which flowers all of January near us, is the bees’ preferred nectar source. In these years we harvest beautiful white, delicately flavoured single-source pōhutukawa — my favourite. The most amazing honeys I have ever tasted, though, are the beech honeys and Tasmanian leatherwood, which has an incredibly strong and distinct flavour. I love how people who really know their bees can taste honey and know exactly which flowers it comes from. Bees have taught me all about all the beautiful tiny flowers in our bush — and I notice their preferences throughout the summer by the sound of their presence.

Q7: What do you hope readers will take away from Conversātiō?

The title of the book, Conversātiō, is also the title of the key work shown in APT9 — a cabinet of wonder, devised to place a colony of bees at the centre of an artwork. I have made all kinds of images of dead bees, but Conversātiō presents the bees themselves as a living image, and documentation of the framed colony of bees inside the cabinet features throughout the book.

I hope the book might be a delight to hold, to read and to look at. Also, that it might amplify the reader’s sense of the beauty of bees and their importance to the health and wellbeing of our ecosystems. The book includes content that spans science, literature and visual art. It includes an essay by an expert on bee vision and navigation who I had the pleasure of working with to devise and test the patterning on a perspex tunnel we created to ensure the bees could be seen flying into the gallery. It also includes a literary work by art writer Gwynneth Porter.

Through working with others, I have learned so much about bee perception: how they see, feel, smell, and how they communicate, do complex mathematics and much else. I am hoping that the presence of bees and people within this book will inspire curiosity and a little bit of wonder.

Q8: The book makes your concerns about the degradation of our environment very clear. The bees are a sentinel, indicators, of that. How so?

Bees are an indicator species, and this has become poignantly obvious over the last 10 years or so through impacts of industrialised agriculture on the honey and pollination industries, particularly in countries like the USA. Bees both there and here are subject to a multitude of environmental impacts from pesticides, fungicides, herbicides, diseases such as nosema and parasites such as varroa destructor. There is also the risk of starvation caused by vast agricultural monocultures and the attendant loss of mixed wild foraging sources. How we manage and control the environment impacts on those species such as bees that we depend on. What is becoming clear is that there are combinations of chemical harms that no one takes account of. The impact of one pesticide might be measured and may be declared safe for use, however the impact of numerous chemicals and the effect of their accumulation over time isn’t accounted for. Bees are an indicator species because it is highly likely that what we are doing to them is most likely the same as what we are doing to ourselves.

Q9: Proud of this book?

The greatest pleasure in creating this book was lending an ear to all the contributing voices. I hope we have done them justice and that it is a book about people as well as about bees and is an enjoyable reflection on a journey to create a collaborative artwork that is accessible both in the gallery and also in this book.

Q10: You’ll always be in love with, and in awe of, bees?

To fear the sting of a bee and know the sweetness of honey — well, that is a marvellous thing. Bees have grounded me in my garden and within my neighbourhood — and, yes, I am always aware they are nearby. That a bee on guard might buzz me when I am digging in the veggie garden next to the hive sets off a primeval urge to run. I love how something so big is attuned to something so small.