Lee Davidson has reviewed Te Kupenga: 101 stories of Aotearoa from the Turnbull

‘Once a year, I take my museum and heritage studies class to the Alexander Turnbull Library (ATL). There we are greeted by a small group of curators who have thoughtfully delved into their treasured collections and selected a few favourite items to show us. Every year I feel a delightful sense of anticipation as to what gems of New Zealand history we will have the privilege of seeing, and which people and events they will connect us with. We never leave disappointed.

Most of the students, like much of the New Zealand public, I imagine, have little conception before their visit of the range, depth and significance of the ATL collections: from rare books to maps, manuscripts, music, oral histories, photographs, ephemera, artworks, born-digital material, even car parts and a rock that have borne witness to significant moments in our history.

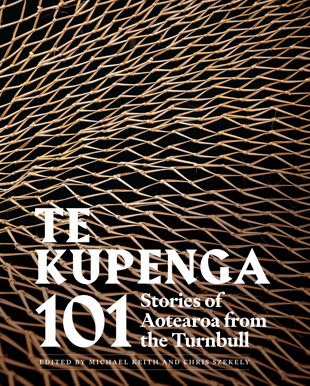

Te Kupenga helps to remedy this. Its many stunning images are the next-best thing to sharing the same room with these taonga. The book features collection items chosen by nearly 40 staff members, who were invited to nominate those that had personal and/or professional meaning for them. The final selection covers a breadth 130 New Zealand Journal of History, 56, 2 (2022) of formats and, as co-editor and Chief Librarian Chris Szekely explains, forms “a multiplicity of windows looking in on, and out of, the library and the country it was established to serve” (p.8).

The roller-coaster journey through the collection starts with a drawing of a rā held in the British Museum, likely the only surviving material example of Māori sail construction from that era, and ends with a Covid Tracer QR code poster signed by Ashley Bloomfield. Between these bookends, readers traverse a mind-bending array of stories spanning immigration, settlement, early interaction between Pākekā and Māori, work and leisure lives, arts and culture, environmental impacts and natural disasters, the Dawn Raids, the 1975 Māori Land March, gay and transgender rights, the gender pay gap, the 1981 Springbok tour, anti-nuclear policy, climate activism and the Christchurch mosque shootings. The “windows” we see through include the perspectives of Māori, women, Chinese migrants, Japanese prisoners of war, refugees, and soldiers, to name a few.

Each item is accompanied by a ‘mini essay’ or story by the curator who selected it. Written in a diverse range of styles, the stories provide key information about the items and their historical context, but they are also a point of departure for reflections on broader themes and trajectories in New Zealand history. These personal journeys into and out of the collections highlight the extent to which our encounters with history and the sense we make of it are coloured by our particular lens on the world.

Valerie Love and Abi Beatson’s story about the Covid Tracer QR code poster, for example, references other public health ephemera dating back to the 1918 influenza pandemic, but also reflects on whether it represents the repurposing of diary-keeping “from the deeply personal choice of recording our actions and reflections, to a practice of collective responsibility that can save lives” (p.248).

Other stories piqued my curiosity about lives lived and their entanglement with the unfolding of history and the legacies we still grapple with today; stories like that of Eruera Pare Hongi, who became a prominent scribe in the 1830s and wrote the Māori text for several important documents, before dying in 1836 while still a young man.

“[We] can only imagine”, Curator Māori Paul Diamond writes, “what contribution he might have made to drafting the Treaty of Waitangi” (p.26). Likewise, the 1899 handbill for a performance by Greek George/Kiriki Hori in both English and Māori — an example of a time when te reo Māori was “a language of civil engagement and Discourse” and “an inspiration for how this could happen again” (p.96). In its own contribution to this aspiration, Te Kupenga includes five essays written in te reo that stand on their own without translation.

Since the library opened in 1920, more than 60,000 New Zealanders have made donations to expand ATL’s original collection, ensuring that it has become a national storehouse that has “relevance and meaning to every New Zealander, enabling them to make connections and find stories that illuminate and intrigue” (p.11). As Szekely also notes, the publication of Te Kupenga coincides with the introduction of New Zealand history as a compulsory subject in schools and what we may hope is a turning point in public appreciation for this richly layered past.

The overwhelming impression the book leaves is that New Zealand history is full of compelling stories, and that having a solid grasp of its complexity and nuances is essential for engaging constructively with the present and shaping a preferred future.’