Q1: The subtitle declares ‘new writing for a changed world’. Changed, how so?

WI: Nature keeps sending out these SOS messages, and Cyclone Gabrielle shows that New Zealand is not immune. Autocratic leaders and militarist regimes in Russia, North Korea, China, Syria, Burma, Afghanistan, to name a few, create instability and hold the world to ransom. So do extremist groups. Look what happened in Wellington.

Twitter, Facebook and other platforms are not safe indicators of what and who to trust. Nor are the usual guarantees of safety: having a house, job, savings, dependable health and good education, food distribution, police to call and other infrastructural systems. These are early warning signs that Te Taiao is failing, our future is mortgaged and we are living in debt. The next generation might turn out to be not better off than ours.

ME: It seems important that we constantly remind ourselves of what we have right in front of us, fleeting as it is: the world we must protect, people we must reach, ideas we must advance. In all ways our spaces are changing at a rapid pace. To cope with this change, we must live in a state of awareness; this is essential. An anthology such as this calls on us to slow down and consider our changed/ changing world from many angles, and to ask more questions about survival, both literal and creative.

Q2: The book is also billed as a hui between writers and artists, and indeed many of the pieces have a participatory feel. What were you seeking to achieve here?

WI/ME: We started thinking about the book three years ago when the global pandemic shut us all down. As the global, glocal and local problems compounded, we felt it important to offer readers a shelter in uncertain times, He Whakaruru-taha. The idea of a hui — or international summit happening in Aotearoa New Zealand, if you like — arose out of that. So when we started to come out of COVID, we decided to ask writers and artists from near and far to come to the summit and offer kōrero about how to future-proof ourselves and our world. But what they tell or show us is only part of the kaupapa taiao of the book. The other part is our invitation, which we are extending now, to readers to enter the kōrero. What do you see of your own futures?

WI: I was also thinking of how, today, moral courage can often look like a tradeable commodity. I looked at A Kind of Shelter as centring the notion within a defined structure among contributors whose views could be trusted.

ME: The idea of the exchange of information is at the heart of this book. There is no lecturing or explaining, but a real exploratory feel — a meeting of minds and hearts, a very special hui. This is most clear in the kōrero that take place between contributors, and I think that space between words and ideas is the heart of the book: where things open up just a little more.

Q3: The book feels very grounded in te ao Māori. How did you ensure that?

WI: I was interested to read journalist Rebecca MacFie’s comment in the Listener that ‘Amid the destruction wrought by Cyclone Gabrielle, marae stand as places of refuge, support and aroha’. From the very beginning, we thought of the marae as our ‘kind of shelter’ within which to ponder the world approaching so swiftly in front of us. Michelle came up with idea of the shelter (drawn from a line of Craig Santos Perez’s poetry). I added to the idea by reimagining it as the haven in the curve of Papatūānuku’s body where her children took sanctuary, during the separation when Ranginui was thrust into the sky, and they were vulnerable to the cyclonic tumult. In the collaborative process we added other elements, notably, Plato’s cave, to the metaphysical construction.

But you’re correct: when designing the shelter or meeting house itself, we followed through with tikanga pertaining to Māori architecture. There’s a koruru, a figurehead or figureheads in our case; a tahuhu, to keep up the roof; heke, or ribs to provide the spatial interior; and, along the walls, carvings and thatched panels representing the historical past and present. In many ways, the shelter represents the taonga that we have all inherited. The contributors might be said to be the keepers or kaitiaki of the taonga. And when the contributors look out at the swirling world before them, they are doing so in full knowledge of the gifts of the shelter or whare.

Q4: It’s a great mix of established writers and new talent. What does that mix bring the collection?

ME: A central purpose of such a collection is to nurture a mingling of voices. At the heart of the project is something quite simple: It’s essential that we listen — to each other, to the natural world, to the abstract forces and energies that inform our everyday lives. Structurally, we saw this as an opportunity to bring together many diverse writers and artists, from some of our most revered, such as Anne Salmond, David Eggleton and Yuki Kihara, to newer award-winning writers such as Nina Mingya Powles, Helen Rickerby and Whiti Hereaka, and also — equally notable — emerging voices such as Faisal Halabi and Cybella Maffit. And what unexpected encounters between Brannavan Gnanalingam and Japanese-French pianist Ami Rogé, between Ghazaleh Golbakhsh and Australian-Italian Catherine McNamara, between Apirana Taylor and Rwandan Louise Umutoni-Bower, for example. Ultimately, we hope this book creates a space for people and ideas to sit alongside each other, eschewing hierarchies for creative flow, inviting reverberations across distance and time.

WI: I think our enthusiasm and that of the contributors is what has contributed to the psychic vitality of the book. With 68 writers, all providing new, fresh, of-the-moment work that hasn’t been published before, there’s bound to be a different, fizzing kind of forward energy and spontaneous combustion. I like to think that there are many pops and explosive moments as you place established writers like Lisa Matisoo-Smith and Patricia Grace against new talent like Wendy Parkins and Day Lane. Or Māori and Pasifika essayists like Alice Te Punga Somerville and Lana Lopesi against Paul D’Arcy and Pip Adam. Getting the mix — or balance — of poetry, prose, memoir, essay and art needed some careful adjusting too. What all these creative thinkers bring to the book gives the book a buoyancy that makes it almost levitate.

Q5: The inclusion of artwork is a delight. Where did that idea come from?

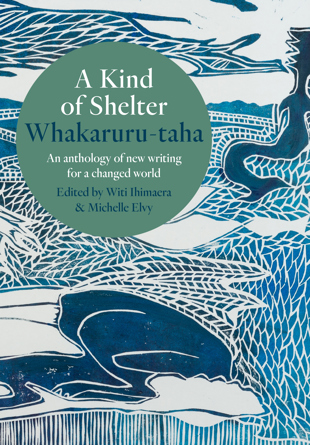

WI: Michelle had always wanted A Kind of Shelter to have a visual as well as written narrative. I trusted to her to select the artists and artworks. In many ways, we could have done A Kind of Shelter as an art book.

ME: We see the artwork as a way to invite readers to breathe in the contents just a bit more: to gaze inward, outward, upward, sideways. We take in the world with our eyes, and so we see this changing world through the eyes of these artists, too. Eight artists are included and their works show the world from new angles: in photography, woodcuts, sculpture, painting and textiles.

Q6: It’s very exciting to see international writers and artists in the mix. How did you pull that off?

WI/ME: Very early on we came up with the notion that we were writing for a greater whole, not just writing for the iwi. So that meant not just being inclusive nationally but also internationally, as if wanderers from afar had happened upon our shelter and we had invited them in to share their kōrero of what was happening to their futures, with us.

We decided to institute a tēpu kōrero in the shelter, rather like the conversation tables at our arts and literary festivals. We thought that these waewae tapu, like Ru Freeman from the USA, Aparecida Vilaça from Brazil, Jose Luis-Novo from Spain and Louise Umutoni-Bower from Rwanda, would create an exciting new ihi, mana and wehi, energy, power and dread, as well as wero or challenge to the New Zealand mindset. To get to your question: we pulled it off with great difficulty. Some of the conversations we tried to wrangle with the assistance of various embassies, some through representative agencies. They had to be done by the facilitators, mostly the New Zealand participants by phone, zoom, email and often with due attention to different time zones. In the case of the conversation between Aparecida Vilaça, Anne Salmond and Witi, we ended up with a Zoom interview that took a month to transcribe.

Q7: These artists and writers are wrestling with the world’s hot-button issues, its ‘wicked problems’. Is there also solace and optimism here?

WI/ME: The contributors have made A Kind of Shelter a big generous haka boogie of a book. We think of it as being a humanitarian document. That doesn’t mean that it doesn’t engage with the perils of living today or being at the mercy of forces we sometimes think we have no control over. There are Māori views, Pakeha, Pasifika, Islamic, Black and Asian that reveal that the book is not only inclusive of New Zealand as a multi-ethnic construct but also that there are a multiplicity of views for the reader to consider. As well, they are from various artistic and professional practices: poets, anthropologists, fiction writers, architects, academics. And they emanate from different age groups and genders including LGBITQ+. I doubt the book would have that moral courage I wrote of earlier if all of our peoples’ views hadn’t been represented in it. But, yes, I think the reader will come away from the summit with a tremendous amount of hope and, most importantly, with a prescription for what being a kaitiaki is, a person who looks after the people and the planet, and how to express it in our everyday lives.

The only reason we keep doing any of our work is for the future, for hope. The work of this project — from the initial idea to the fine-tuning and many pages of proofs — is worth the effort because at the end we hold something valuable in our hands: something precious that is a collaborative expression of our selves. This is the very heart of the creative process, for me: an invitation to engage, with a view that simultaneously looks outward and forward, asking ourselves to be our best selves, our most generous selves. This is a project with grave contents but ultimately full of hope. There is no other way.

Q8: How does a Māori approach steady our currently very rocky boat?

WI: New Zealanders are beginning to understand the value of mātauranga Māori. A Kind of Shelter, itself, is arranged according to the principles of whaikōrero. It begins with a karakia from Hinemoa Elder, various kōrero from Apirana Taylor, Ben Brown and Emma Espiner, and waiata, pakiwaitara, pūrākau and poroporoaki from others.

I mentioned earlier that the shelter represents the taonga that we have all inherited. The Māori contributors could be said to have a vested interest in being kaitiaki of the taonga or living repositories of it. If you think of the book as a piece of greenstone, they add to its dimensionality. I personally see their roimata toroa, flecks in the pounamu, their traditional insights or refracted wisdom or perspective that we the tribe — and Aotearoa New Zealand — needs to hear or know. A Māori approach gives the country transformative power to make our ways into the future more achievable and enriching — and to look after the iwi while doing it.

Q9: Do you think this anthology breaks new ground, and how?

WI: A Kind of Shelter is not only a national summit, but also a unique and distinctive international one. We’ve had great anthologies of Māori, Pasifika, Asian, gay and women, sci-fi, environmental writing, among others, but this anthology, I believe, is the first of its kind. It incorporates all types of writing, positions Aotearoa New Zealand as a marae for the future and it empowers so many voices from so many places to speak out to the world with strong and vigorous kōrero. It has built for itself a truly unique and innovative marae from which to hui from.

ME: I think most anthologies that take, as their starting point, a critical and creative view of our world are offering something new and important. Look at, for example, No Other Place to Stand (AUP 2022) or Ko Aotearoa Tātou | We Are New Zealand (OUP 2020): both of those books were born of necessity and carry important messages for our world, and for the wider world. With regard to this collection, I echo what Witi says in that this is not merely in response to what we sense around us, but moves, structurally and imaginatively, beyond, in the way it presents a space to debate, examine and exchange and also a place to offer new visions and yes, even hope. Even as the editor who has pored over the contents so many times, I find something new each time I pick it up. It feels like a living, breathing thing, to me.

Q10: What do you hope readers will take from its pages?

WI/ME: For New Zealanders, that the ‘we’ we used to think we were has now become a more inclusive ‘us’; we are tatou now. That our pūtake or taproot into Māoridom gives us tremendous mana, strength. That our many other mātauranga give us resilience and transformative power. Our potential as humanitarians looking after ourselves and our planet is unlimited. Together, we are amazing. And we have a new generation to do our work for: the mokopuna.

This flows beyond our borders, too: we are reaching out to the world, from here, and opening a door. This is not an inward-gazing project but one that sees shared energies as the most powerful part of our creative potential. We hope readers will step inside and feel welcomed, and also carry their own new ideas, inspired by the pages here, as they walk their paths around/into/with the world.