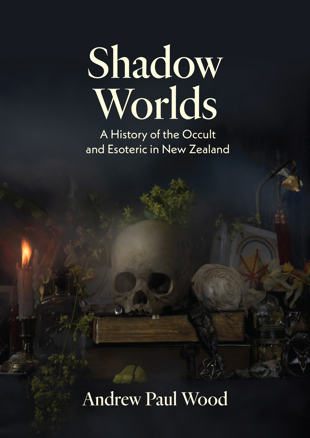

Jack Ross reviews Shadow Worlds: A history of the occult and esoteric in New Zealand by Andrew Paul Wood:

‘Whose attention would not be caught by the following book title: The Blue Room: Being the absorbing story of the development of voice-to-voice communication in broad light with souls who have passed into the Great Beyond by Clive Chapman (published in Auckland by Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd in 1927)? I first came across a reference to this curious book in another obscure publication, D. Scott Rogo and Raymond Bayless’s almost equally intriguingly titled Phone Calls from the Dead, which fell into my hands in 1979. Shortly afterwards I managed to acquire a copy of The Blue Room and was thereby privileged to read its long and ‘ghost-written’ account of ‘Uncle Clive and his careful fostering of the clairvoyant abilities of his young niece Pearl’—by a reporter identified only as ‘G. A. W.’

Information about this particular sequence of séances came to an abrupt end in the year 1927, following the publication of Chapman and G. A. W.’s books. Thereafter, nothing. So I was delighted to find some supplementary details about the case in the chapter entitled ‘Bumps in the Night’ in Andrew Paul Wood’s sleuthhound history of the occult and esoteric in New Zealand. He records, for instance, a reference in Harry Price’s Fifty Years of Psychical Research (1939) to an incident ‘around 1930’, where: ‘William Henry Gowland (1879–1965), professor of anatomy at the University of Otago’s medical school, witnessed heavy tables levitate and a locked piano play itself.’

An Otago Daily Times reporter invited to an earlier séance said of the phenomenon he witnessed: ‘If it was trickery, it was damnable trickery, for there were many in that Blue Room who believed, heart and soul.’

This is perhaps the most useful feature of Wood’s book: its inclusiveness and the fact that he’s followed up on so many intriguing details of early New Zealand occultism—as far as that’s possible in so tantalisingly ill-defined a field. Nor does he scruple to record the many occasions where the trail has run cold, and the rumours of the continued existence of some exiled order or malign coven cannot be substantiated one way or the other.

It’s true that much of this data is not, in itself, particularly interesting or stimulating except to bonafide enthusiasts or other academic researchers—although it does confirm, amongst other things, that people in New Zealand in the years after World War I, like those in other countries that suffered many casualties, were obsessed with making contact with the dead. Nevertheless, much hard-to-find minutiae is given space: the list of changing addresses for the Dunedin Theosophical Lodge between 1914 and 2015—recorded in detail on pp. 61–62 of the chapter devoted to this ‘Not-so-secret Doctrine’—is fairly typical of this aspect of Shadow Worlds. If in doubt, include it, appears to be the guiding principle—after all, it might be of use to someone—which led me to wonder, at times, if simply compiling an encyclopaedia of New Zealand esotericism might not have suited Wood’s (and our) purposes better?’

Read the full review here.