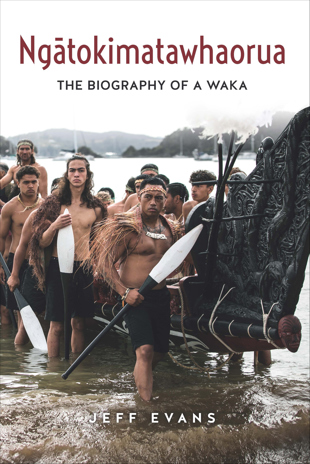

Danny Keenan (Ngāti Te Whiti o Te Ātiawa) reviews Ngātokimatawhaorua: The biography of a waka by Jeff Evans:

'Jeff Evans’s Ngātokimatawhaorua is an illuminating history of the 35.7-metre-long waka taua (war canoe) Ngātokimatawhaorua, which, for the most part, has stood quietly in the Treaty grounds at Waitangi, Aotearoa New Zealand. Sheltered under the waka (canoe) shelter Te Korowai ō Maikuku near Hobson’s Beach, Ngātokimatawhaorua has long piqued the interest of visitors walking by, on their way to the Treaty House, the Te Whare Rūnanga meeting house and the spacious grounds overlooking Pēwhairangi Bay.

Built for the 1940 Treaty of Waitangi celebrations, this giant war canoe represents a “powerful symbol of Māori identity, strength and pride” (p. 8). Evans’s engaging account contains “dual lines of history and significance for Northern iwi/Māori”, writes Pita Tipene, chair of the Waitangi National Trust (p. 6). The first Ngātokimatawhaorua was an ancestral waka that journeyed to Aotearoa. It was re-adzed by legendary Polynesian explorer Kupe “to complete the return trip to Hawaiki” (p. 6). Ngātokimatawhaorua’s reincarnation in 1940 drew on these whakapapa (genealogical) and tupuna (ancestral) connections, as does this first book on Ngātokimatawhaorua, which can therefore be seen “as a biography rather than a history” (p. 6).

This interesting point is not really developed here, though it recalls the work of scholars like Joseph Hetekia Pere of Te Aitanga a Māhaki who, in writing of his forebears and their egregious losses, framed his writing in order to honour those tūpuna, because they had left descendants with a “an obligation and an undertaking to faithfully preserve taonga [treasure] of the history of Mahakai iwi [tribe]” that included stories of important people, places and defining events across millennia (Pere 1991: 30).

This undoubtedly included, as Teurikore Biddle has written, the development of an organic expressional and material culture through which significant histories of voyage, discovery, adaptation and cultural integrity were enshrined and celebrated (Biddle 2012: 58)—waiata (songs), haka (posture dances), tauparapara (incantations to open a speech) and, not least, waka taua as commanding as—in this case—Ngātokimatawhaorua, itself grounded by Ngāti Rāhiri and Ngāti Kawa of Waitangi who, linked through Pouerua Pā, descend from that ancestral waka. Ngātokimatawhaorua is now the preeminent waka of Te Tai Tokerau iwi, adds Tipene, and, as the largest ceremonial waka in existence, is of national significance (p. 6).

The origins of the waka taua Ngātokimatawhaorua are interesting, recounted by Evans in a lively and compelling manner. Much of the credit is given to Te Puea Hērangi, who championed the construction of Ngātokimatawhaorua in the mid-1930s. Te Puea’s original vision included several carved meeting houses and seven waka taua, each one representing one of the seven original waka of the major tribal groups. Waka taua sit at the pinnacle of traditional Māori waka design, writes Evans, a design and material adaptation made necessary because of the new terrain of Aotearoa, and made possible once tūpuna began exploring the primordial forests, isolating an abundance of “very large, very tall trees, particularly kauri and tōtara” (p. 9). Ngātokimatawhaorua itself originates from the depths of Puketi Forest. Te Puea sought assistance to launch her vision from Piri Poutapu, a tohunga tārai waka (expert canoe builder). But because Piri was young, Te Puea turned to Rānui Maupakanga, who had once constructed a waka taua for her grandfather, the renowned King Tūkāroto Matutaera Pōtatau Tāwhiao. Rānui, now in his seventies, was possibly the last master waka builder of his generation. His formidable task was to locate at least two kauri trees suitable for the construction.

Ngātokimatawhaorua was carved as a partner to Te Whare Rūnanga at the Treaty grounds. Many of the same carvers who had devoted their expertise to Te Whare Rūnanga also worked on the construction of the new waka taua. Ngātokimatawhaorua first appeared in 1940. Few gathered on the beaches that day, writes Evans, expected to see the beauty, grace and majesty of the waka taua crossing the harbour; “the crew aboard the giant waka revelled in the occasion, surging across the harbour as their ancestors once had, their white-tipped hoe [paddles] flashing against the calm blue water” (p. 126). Following its grand display on 6 February 1840, Ngātokimatawhaorua’s future was far from assured. The waka was dismantled after the commemorations and relocated to the upper Treaty grounds beside Te Whare Rūnanga, where it would reside for the next 34 years. This all changed when kaumātua (elders) successfully argued for its restoration in time for Queen Elizabeth’s visit in 1974. Ngātokimatawhaorua also attended the centennial celebrations in Whangaroa County in 1987.

Queen Elizabeth also visited Waitangi in 1990, as part of New Zealand’s sesquicentennial celebrations. With 1990 proclaimed as the Year of the Waka, the New Zealand Kaupapa Waka Project was launched, inspired once again by Te Puea Hērangi, who, it was recalled, had wanted to restore and build waka taua as an expression of the tribal prestige of all Māori.

Now, on a scale much grander than Te Puea could have imagined, with toki (adzes) and whao (chisels) succeeded by steel tools and treated timber, waka were constructed by hapū (subtribes) and iwi all over Aotearoa for the occasion. On 6 February 1990, alongside countless vessels, boats, yachts and pleasure craft, a flotilla of specially constructed waka from all over Aotearoa, led by Ngātokimatawhaorua, sailed across Pēwhairangi Bay. Such waka taua had become a symbol of Māori unity and pride in this important year of remembrance. According to some Māori, they were seen “as the vehicle which [would] carry the mana [spiritual power] of Maoridom into the new century” (Buddy Mikaere, cited in Keenan n.d.). Such was the legacy of Ngātokimatawhaorua.

Ngātokimatawhaorua provides a well-researched, multilayered and lavishly illustrated history of the waka taua and the exhaustive processes by which it was envisioned, designed, constructed, displayed and preserved. Evans’s account of the commensurate traditional and ceremonial elements associated with all aspects of Ngātokimatawhaorua’s creation are adeptly compiled and especially compelling. Evans’s style—and journey—is both historical and personal, much in the style of noted historians like Peter Wells, building on a polished proficiency, as seen in his previous works, including his accomplished biography Heke-nuku-mai-nga-iwi Busby: Not Here By Chance (Huia, 2015), Waka Taua: The Maori War Canoe (Oratia, 2017) and Maori Weapons in Pre-European New Zealand (Oratia, 2014).

As Pita Tipene correctly concludes, Evans “carefully binds together the different parts, people and time periods”, exemplifying the way in which the waka builders and carvers themselves “worked to shape, bind and lash together” (p. 7) all of the elements that, when all fused together over time, created this astonishing cultural icon, Ngātokimatawhaorua.'